An odyssey that ends 65 below zero

Summary:

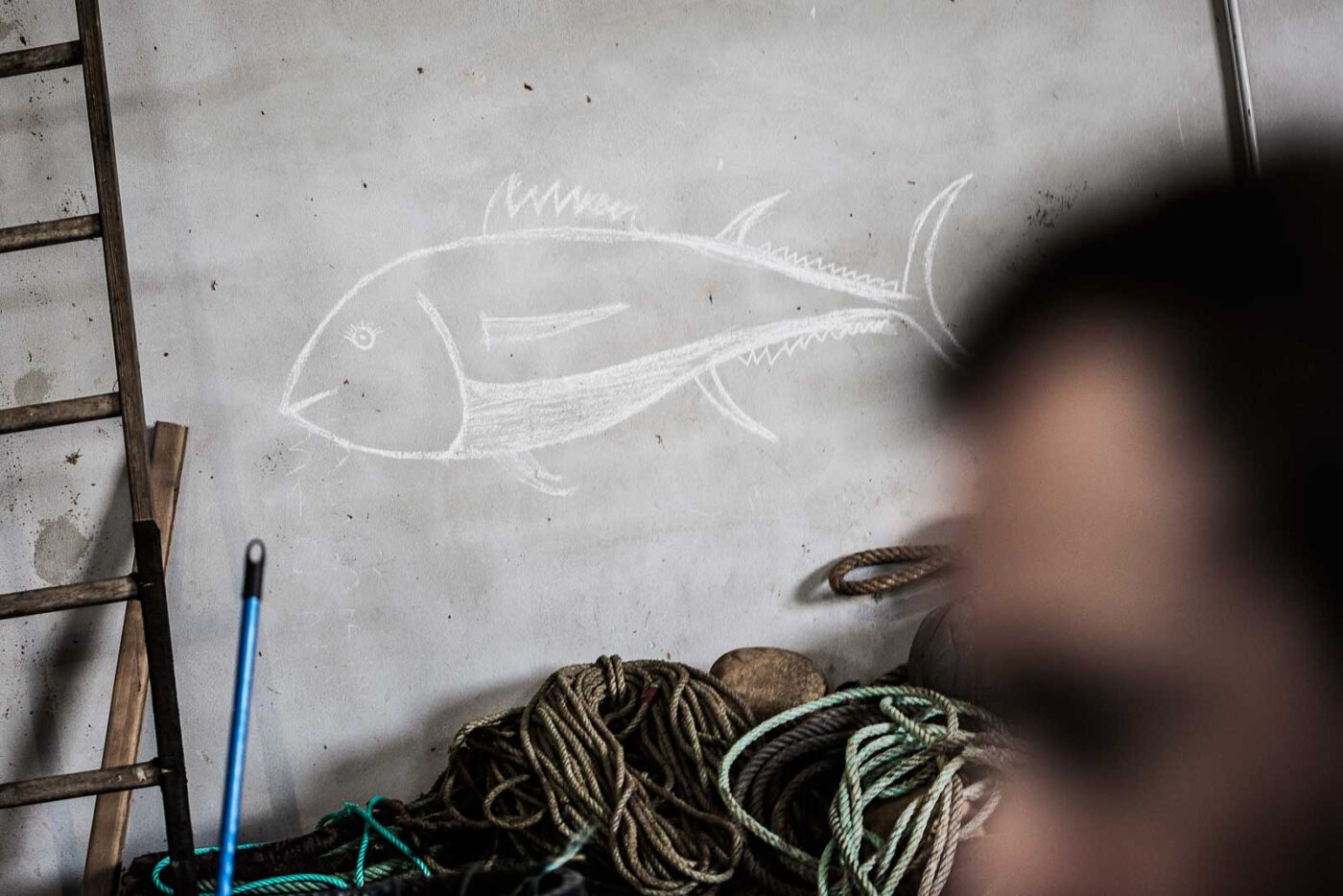

On the grey, somewhat pitted wall, alongside a tangle of discarded nets and fishing gear, the eye is drawn to a tuna with a Mona Lisa smile, drawn in chalk. There is a somewhat childlike air to the pictured fish, the outline clearly defined, with a bulging silhouette, like some cave painting to which these muscular men of the sea pay tribute each morning before they step into the changing room. Sacred tuna, totem of the sea, I entrust myself to you.

In the warehouse of the Barbate pound net, the mariners wait for the sun to shake off its slumbers, chatting away calmly before the clock has even struck seven. Little by little, they change into their orange overalls, and sip steaming hot coffee. The drinks dispenser also has its own shrine: a poster of Mágico González, star of Cádiz F.C. in the 1980s, and for the locals, a somewhat rebellious maestro who was better than Maradona himself. All is mythologised. Straits. Barbate. Almadraba. As they ironically say around these parts, in an expression that has no equivalent in Japanese, casi ná – scarcely a thing.

Almadraba stories

The almadraba pound net of Pesquerías de Almadraba provides 70 jobs in season, and has been under the management of Cartagena’s Atún Rojo Fuentes 50% since 2018. With his salt-and-pepper hair, somewhat weary of the brine and the ups and downs of life, raised in Conil de la Frontera, Miguel Muñoz Ruiz is the captain of this tale of Barbate, this ages-old destiny of nets and lures. “My knee is shot from fishing tuna, a war wound, but we’ve been here on the frontline since 1984. My father worked the almadraba net before me, as a sailor. He got me into this. It’s all changed a lot. The machinery is more modern now, the boats are made of fibreglass, and above all the fish doesn’t suffer, or even realise…,” Miguel recounts before boarding the fishing boat, with its six masts and anatomy of wood, painted blood red and pistachio green.

I am told round here that this season is turning out wonderfully. There are more and more tuna. Too many tuna, some say. So many that on occasion the school tear through the nets, like the string of the kite. The fish caught this May morning are of a good size, between 180 and 250 kg. In 2022 over 1,100 tuna have been plucked from a migratory journey which ends in these nets. Overall, Barbate’s share this year amounts to 408 tonnes, increased this year to 1,113 tonnes thanks to the transfer of other fleets (Fuentes handles a total of 17,000). As soon as we clear the breakwater we see the tip of the almadraba net, barely a nautical mile and a half from the shoreline. “Over the last few days we have put a whole load of fish in the pool alongside the net. There must be a thousand or more tuna in there now. Early every morning, we pull up the net and the divers go in to slaughter the fish.

We bring them up on board, and try to make sure that no more than an hour passes between the fish being slaughtered and having their loins and bellies deep-frozen,” explains David Martinez, assistant manager at the Ricardo Fuentes Group, with hundreds of angling battles to his service record (he has been at the company since 1999).

Last stop for the bluefin tuna: the freezer ship

His words are carried on a light easterly wind which doesn’t trouble us today, against the backdrop of a freezer ship lying just 500 metres from this undersea labyrinth of nets and anchors. The ship has been leased by Fuentes and measures an imposing 100 metres and more in length, with a crew of 33 from Indonesia, the Philippines and other distant climes hard at work with their knives, slicing up each fish with the respect and precision of a surgeon, as they arrive like clockwork from the transport boat.

On board this behemoth, under a white canopy to protect against the blistering sun, the Fisheries Inspector draw up his report and check that the whole process is performed in accordance with the legal parameters. He notes down the weights and count the fish, just before these now lifeless colossi are sliced up.

To 65 below zero in 15 hours

And straight away, the keen knives of the processing section carve through the fish in a matter of seconds. Slash and slice. Perfectly neat loins and bellies, scarlet red, tumble down the slides leading them directly to the freezer chambers. There is plenty of room to spare in these compartments, which make Siberia seem like a summer resort. In the cold stores, photo and video equipment wouldn’t last a second. They use pencils in there, as ballpoints freeze and become useless. You have to wrap up as warm as possible to ward off hypothermia. The hairs of your moustache will turn to stalactites before you know it.

This deathly cold is the healthiest possible process for the 4,000 net tonnes that the ship can carry. And every day, around 60 tonnes are brought on board. “In around 15 hours they get the temperature down to 65 below zero. What I like about this tuna is its colour, its quality, flavour, the intrinsic fattiness, but above all its freshness, because Fuentes focuses on processing it quickly,” explains Go Kumazawa, who buys and distributes these treasures of the deep, which will end up being sent to every corner of the globe, whether a fancy restaurant in Paris, an izakaya in Boston, or a sushi bar in Yokohama. “Spain’s almadraba nets have a real reputation worldwide. A lot of my customers really like them,” Go adds.

The freezer ship has cast anchor in these waters until the meteorological summer begins. It will be calling at Cartagena, Malta, Tunisia… And will then pass through the Towers of Hercules and set a course for my beloved homeland of Japan. That will be when the white snow settles on Mount Fuji, and the tuna swim happily in the North Atlantic, without yet having embarked on this legendary migration.