Every Japanese term, everywhere

Summary:

A logbook by Sensei Hiroshi Umi.

According to an old Spanish proverb, “you are not from where you were born, but from where you graze” (or where you choose, I would add). Roger Ortuño Flammerich was born into this world in Barcelona, his surnames reveal roots in Navarre and Catalonia, and he has relatives in the Vega Baja region on the River Segura in Alicante. But you could say that Roger is a displaced Japanese, born not in Tokyo but some distant place, for reasons of destiny and cosmic fate. A noble figure, with a big-framed, imposing presence, whose immersion in the cuisine and expressions of Japan (see his blog and portal comerenjapones.com) has been so complete that sake runs through his veins, while the helixes of his DNA are interwoven with koji.

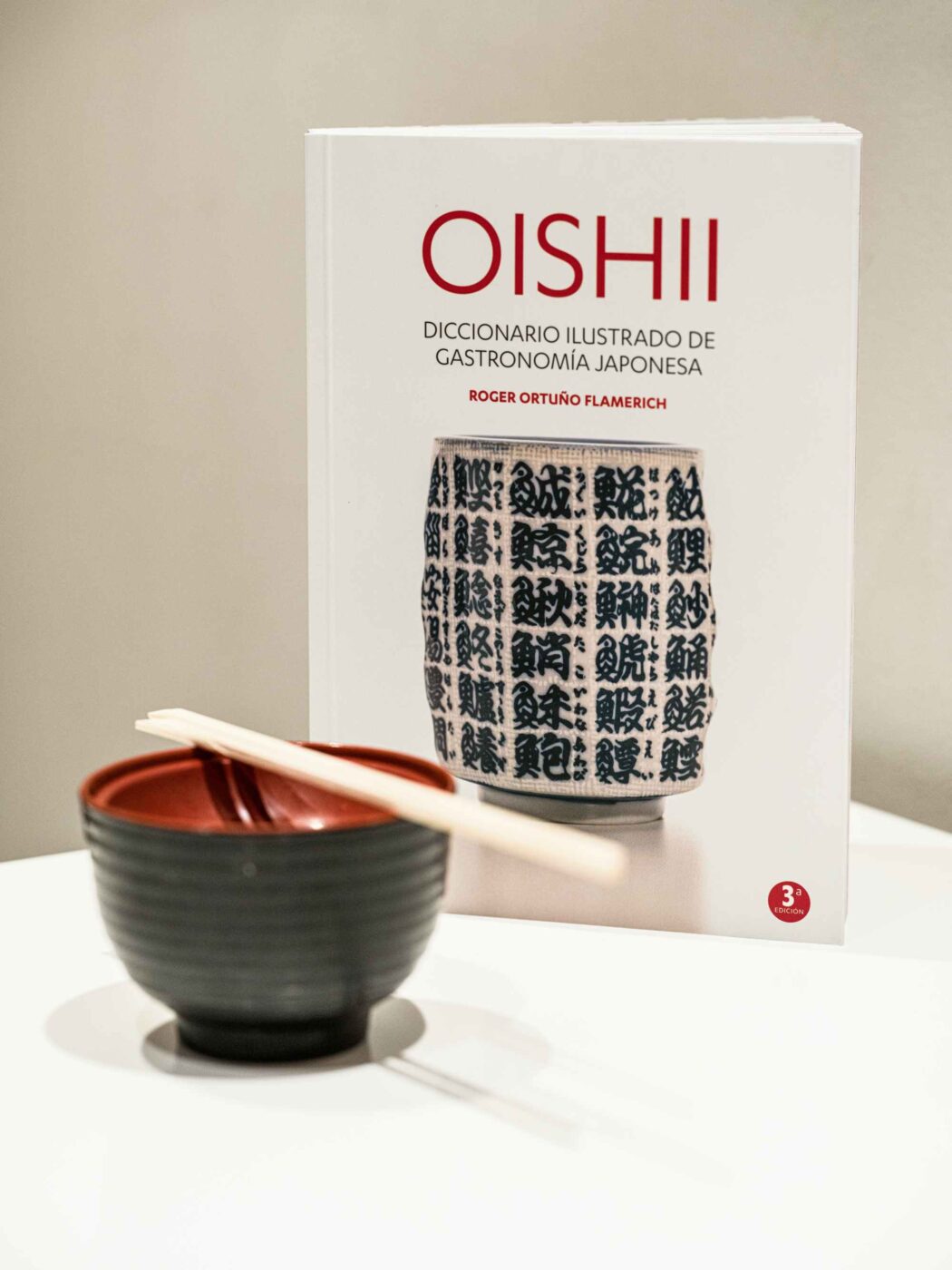

We met up with this sommelier, consultant, adviser, conference speaker, goodwill ambassador for Japan and lifelong gourmet to eat some nigiris, now that his Oishi. Illustrated Dictionary of Japanese Gastronomy (published by Satori) is in its third edition. We took the opportunity to find out about his traceability, his preferences, succulent bluefin tuna, his immediate plans and his life as a publicist turned Japan expert. He claims that he speaks Japanese poorly, but writes it well. He will shortly be turning the page on his first half century of life. A landmark birthday that he will be celebrating with a new book under his arm, well fermented with words, flavours and places…

Given your success and impact, you even have your own entry in Wikipedia, Mr Publicist.

The Wikipedia thing was entirely spontaneous, to be honest. And you can’t change a thing, not even a comma, even if there is a glaring mistake. They penalise you if you try to. If anything is wrong, you have to wait for an editor to correct it.

There must have been something that triggered this great Japanese epiphany which has made you famous…

I’m from Barcelona, I grew up in Las Corts. When I was 12-13 years old, a friend of mine had a Casio watch with a keyboard, which could write a kind of tele-type. You could use its alphabet to transcribe in katakana (one of the two forms of Japanese script, along with hiregana). And so it all began with that fascination, but like a game, like deciphering hieroglyphics. And so I began leafing through a Japanese-Catalan dictionary, and thought to myself: ‘I wonder how many words I know? Katana, kimono, tatami… And so I began to study the language and note down all the new words I came across. If you ask me to name a culinary epiphany, that would be in 1991, eating okonomiyaki (dough with different ingredients on top), and going to the first Japanese restaurants in Barcelona, of which there were very few.

The origin

And little by little, comerenjaponés began to take shape. How did it all come to fruition?

It was the blog that gave rise to the website. I wanted to create a really detailed search engine of recipes, dishes, restaurants… Rather than having it all jotted down in a notebook, I made it in digital format for myself and others to consult. It was quite by chance. These days my blog is a little neglected, because everyone uses Instagram now.

How long did it take you to write the dictionary, which is now in a new edition?

A fair few years. I had been building up glossaries since 1991. People hadn’t even heard of Kabuki back then.

The title of your work is illuminating, as it means “delicious”…

My dictionary is a tribute. Oishi means delicious, yes, but it also pays homage to the manga Oishinbo (111 volumes between 1983 and 2014), where two journalists seek the definitive menu, the most delicious products in the world among producers, farmers, fishermen… There is a seven-volume anthology in Spanish, with individual stories covering seven themes of gastronomy. The translator asked for my help with the culinary terminology. I found some very subtle mistakes in the characters. Oishimbo resulted in an 800-word glossary. When we translate, we try not to lose the essence of each word. I have also been involved with manga comics telling the story of the Mibu-elBulli meet-up (Norma Editorial).

Bluefin tuna

Let’s talk about tuna, which has plenty of terminology in your dictionary: what form does Roger Ortuño find most entrancing?

We have organised plenty of ‘ronqueo’ tuna butchery demonstrations in Barcelona and elsewhere. I really like the belly, the toro. But I prefer it if I can combine it with rice, in a nigiri, a tekkadon, a donburi… because it feels that it goes further. And then the kama is another amazing cut. The kama, the bone from the jaw here, attached to the start of the belly. That is quite something done in the oven. A little while ago I tried a battered, fried cheek and a heart, sliced like ‘mojama’, with a texture like beetroot, raw and macerated. The head, the kabuto, is also very popular cooked in the oven. You can use practically every bit of a tuna, I love that. The meat that you scoop from the backbone, the nakaochi that you have to scrape out with a spoon, is wonderful for temaki. If you go to the market in Toyosu, as in Tsukiji previously, you see that a lot of places mark their tuna as hon maguro (blue fin) from the Mediterranean, and that is seen as a prestigious product.

As a consultant, where have you eaten the most spectacular Japanese food?

At the market stalls in Tsukiji. I’ve been to Mibu several times, and they can really hit the heights with a simple turnip soup or a bare-bones sushi. I remember a dish made with the pod of the soramame, a type of bean, which I found really moving, because my wife was pregnant and my mother had recently passed away; it symbolised a tribute to mothers, and the way it was presented was quite incredible. Another spectacular place is Ryugin, in Tokyo, which is out of this world (run by Seiji Yamamoto, with three Michelin Stars). It’s all about kaiseki dining, taken to the next level, a signature approach, with flambéed, cured and toasted bones, meat macerated with kombu… Every last element on the plate has its own special treatment, and a different technique for each dish. Unrepeatable. With liturgy and in a logical sequence. In Barcelona I really like Suto, in Las Corts, which has a Michelin Star. I like that, because it has finally achieved recognition.

Your new book will soon be casting a little more light on the world of sake.

Satori are bringing that out for me again. They publish manga, a cultural dictionary, haikus… they’re real purists. It’s taken me years, and I’m finishing it now. And there won’t be anything like it, a complete encyclopaedia. With more than 120 varieties of rice, with tasting notes, where the crosses come from, where it was developed… Species, subspecies and varieties, types of water, yeasts…

There are books in English, in Japanese… from Canada, from the USA, but I wanted to go much further, with more than 30 different sources. I compared things in seven different books to arrive at the essence, and question a lot of aspects.

Is it possible to make great sake outside of Japan?

Ask a paella purist if you can make great paella outside of Valencia.

If I go to your home, what would we eat to celebrate your book?

I’m impatient, always in a real hurry, so I make quick, systematic things, that almost take care of themselves. I don’t have the patience to go through all the steps that Japanese cuisine requires. I like to do roast chashu chicken, macerated and thinly sliced, ajitsuke tamago eggs cooked at low temperature, macerated in a specific broth.